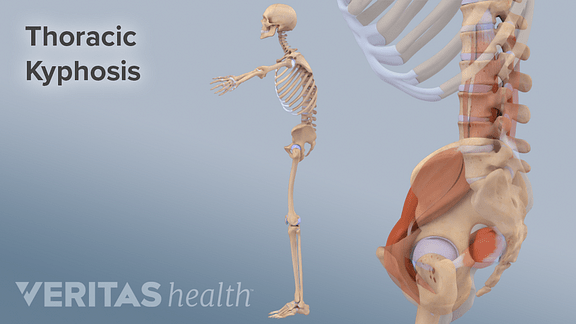

When a patient is observed to have an increase in the normal curve of the thoracic spine, the patient is described as having a kyphotic posture. Such a posture is most easily observed when viewing your client from the side. An overgrowth of fatty tissue in the cervicothoracic junction is often present, perhaps a response to this posture and the associated soft tissue imbalance.

Kyphosis is a posture associated with aging and is frequently observed in elderly patients. There is a marked increase in the kyphotic angle after the fifth decade (O’Gorman and Jull 1987). Hyperkyphosis is a kyphotic angle greater than 40%. Health outcomes associated with this posture include thoracic back pain, restricted range of spinal motion, functional limitations, respiratory compromise and osteoporotic fractures (Greendale et. al. 2009).

The relationship between head position and the thorax has been investigated, and some researchers have found that as the head moves more anteriorly there is an increase in curvature from C7 to T6 (Raine and Twomey 1994). People who retain static work postures when seated at desks or when driving, or when carrying out tasks that encourage craning of the head, often portray kyphotic spines.

Consequences of Kyphotic Posture

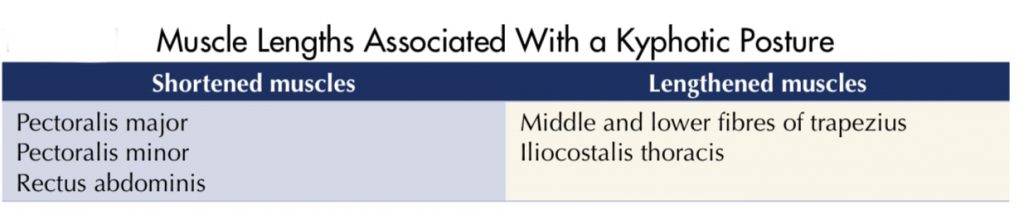

Kyphotic posture with an increase in the normal curve of the thoracic spine. There is compression of the anterior longitudinal ligament and lengthening of the posterior longitudinal ligament and compression of the anterior aspect of interverte- bral discs. Muscles and soft tissues on the back of the body (spinal extensors and the middle and lower fibres of trapezius) are lengthened, whilst those on the front of the body (pectorals and abdominals) are shortened. It has been postulated that the signifi- cant increase in load on the L5-S1 intervertebral disc could be a contributing factor in lumbar disc pathologies, progression of L5-S1 spondylolisthesis deformities and poor outcomes after surgery (Harrison et al. 2005). The increased activity in thoracic spine extensors could contribute to fatigue of these muscles and thoracic pain. This posture is likely to affect shoulder movement. For example, a large kyphosis has been associated with reduced arm elevation in older patients (Crawford and Jull 1993)

KYPHOTIC POSTURE TREATMENT

Before treatment, note that caution is needed when attempting to address a kyphotic posture in certain client groups:

■ Clients with or at risk of having osteoporosis (e.g., elderly or anorexic clients or clients formerly anorexic or bulimic). This is because some activities that encour- age extension of the spine place stress on vertebrae and are therefore potentially harmful in patients with brittle bones.

■ Clients who have recently had surgery to the chest or abdomen. Extension of the spine lengthens tissues on the anterior of the body and could affect wound healing.

■ Clients whose postures are protective in nature, adopted consciously or uncon- sciously in response to emotional sensitivity (e.g., fear, anxiety, shyness, depres- sion). Extension of the spine is a physical opening up of the anterior of the body and can leave some clients feeling emotionally exposed.

What You Can Do as a Therapist

■ Acknowledge that interventions may be limited where the kyphosis is the result of degenerative changes rather than the poor posture associated with slumped positions.

■ Help your client to identify causal factors and correct her own posture. The sorts of activities that could contribute to this posture are prolonged hunching when gardening, sitting at a desk, driving, rowing, playing computer games, and doing close work such as drawing, needlepoint or illustration.

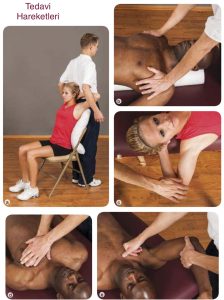

■ Passively stretch shortened tissues (in this instance, the pectorals). You could face the client to perform this stretch, or, for greater leverage, you could stand back to back. Take care not to overextend your client’s spine; concentrate on extending the client’s arms rather than arching the back. Spine extension is impor- tant, but trying to facilitate this whilst also stretching pectorals risks overstretching. One way to lessen the chances of this and to make the stretch more comfortable is to place a pillow behind the client. Take care not to overextend the shoulder.

■ If stretching the tissues with the client in the supine position, adding a bolster or pillow positioned longitudinally against the thorax enables you to extend the shoulders slightly and thus facilitate a greater stretch for those clients for whom this is tolerable. Take care to also support the head and neck. If the bolster is too firm, it can be difficult for the client to remain resting on it comfortably because there is a tendency to roll to one side unless equal pressure is applied to both shoulders.

■ When treating a client with a shoulder condition where depression of the affected shoulder could be uncomfortable or even contraindicated, the supine chest stretch could be performed unilaterally. To do this, your client will need to be positioned diagonally across the treatment couch so that she can extend the shoulder on the side of the chest to be stretched. In this particular example the client has placed her hand behind her head, and you will discover that altering the position of the arm localizes the stretch to a different portion of the pectoral muscle .

■ Using the same positions that you use to stretch muscles passively, you could apply muscle energy technique.

■ Massage shortened tissues. Many clients feel comfortable with receiving massage to the clavicular portion of the pectoral muscle. The client can be supine, a position in which you have greatest leverage on this tissue. Where massage of the whole chest is acceptable, concentrate on stretching tissues from the sternum to the shoulder by using less of your massage medium than normal .

■ To enhance the stretch of chest tissues, you could use soft tissue release. Holding your client’s arm so that the shoulder is flexed at about 90 degrees, lock the chest tissue using your fingers or fist, gently pushing the tissues away from you. Maintaining your pressure, slowly abduct your client’s arm, passively stretching the tissues. in which the therapist passively abducts the client’s arm. This technique works equally well if the client abducts her own arm, moving it in such a way as to localize the stretch to different parts of the pectoral muscle by varying the degree of abduction.

■ Address alterations to the position of other upper-body parts that are associated with kyphotic posture, in this case forward head posture ,protracted scapulae and internal rotation of the humerus.

What Your Client Can Do

■ Identify any factors that may contribute to the maintenance of a kyphotic posture and avoid these  where possible. Not all of the contributing factors may be avoid- able. For example, where there are degenerative changes to vertebrae. Pay particular attention to posture when watching TV, and avoid slouching. Avoid hunching over a steering wheel or desk. When using a laptop position this to avoid a slouched posture and wherever possible use a detachable keyboard. Follow the advice for the correct set up of electronic display screen equipment .

where possible. Not all of the contributing factors may be avoid- able. For example, where there are degenerative changes to vertebrae. Pay particular attention to posture when watching TV, and avoid slouching. Avoid hunching over a steering wheel or desk. When using a laptop position this to avoid a slouched posture and wherever possible use a detachable keyboard. Follow the advice for the correct set up of electronic display screen equipment .

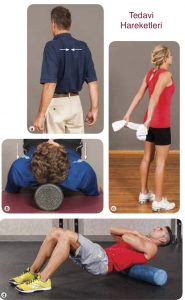

■ Actively stretch shortened muscles, in this case the pectorals. Contraction of the rhomboids is a simple method of stretching pectorals and has the advantage that it can be performed surreptitiously almost anywhere.

■ Where chest stretches prove to be uncomfortable, a client could rest supine with a bolster or pillow placed longitudinally along the length of the thorax allowing the arms to relax. As the scapulae relax into a neutral or retracted position, tissues of the anterior chest wall stretch. Clients with pronounced kyphosis may struggle to adopt this resting position and might even find it uncomfortable because it encourages both extension of the spine (from the normal or exaggerated kyphotic curve) and retraction of the scapulae. In such cases, simply resting supine in the floor will encourage correction of the spine, unless this is anatomically fixed.

■ Some clients find it helpful to hold a small towel, thus stretching the anterior of the shoulder joint also.

■ A wall or doorframe can facilitate a chest stretch where a client has a shoulder problem and cannot stretch both shoulders and both sides of the chest simultaneously. Try this for yourself. Notice that if you place your hand against a wall, elbow extended, and then turn your body away from the wall, the stretch can be localised to various regions of your chest when you raise your arm, sliding it up the wall before starting the stretch. Some clients find this too strong a stretch. Holding a vertical bar (rather than touching a wall) reduces the stretch because when holding a bar the fingers are flexed and the wrist is more neutral, whereas with the palm against the wall the wrist and fingers are in extension.

■ Strengthen the middle and lower fibres of the trapezius and the rhomboid muscles to help retract scapulae, using exercises such as the dart and prone rhom- boid retraction. Aim to increase the duration the client can hold the position in each exercise pose. For prone rhomboid retraction, ask your client to rest face down and to abduct the arms to about 90 degrees. Next, ask him to gently lift the arms off the floor and supinate the forearm so that the thumbs are pointing upwards.

■ Use a foam roller to facilitate spinal extension .Use extreme care because these rollers are made of firm Styrofoam; used in this manner, they place considerable pressure on individual vertebrae. This would be contraindicated for anyone with osteoporosis or a history of thoracic spinal pathology (such as joint subluxation or disc herniation). Clients with inflammatory conditions should use caution.

■ Practice sitting up straight when performing seated tasks. It is not surprising that many people slouch, increasing the curve of the thoracic spine, because upright sit- ting requires more effort as evidenced by an increase in activation of thoracic spinal extensors compared to other seated postures .

■ Performing yoga may help to correct kyphosis. Patients who adopt the mountain pose stance in yoga have been found to have a more correct stance, that is, a more symmetrical posture (in both frontal and transverse planes) than when in the relaxed stance. Not surprisingly, those who have been practicing for longer and more fre- quently demonstrate greater symmetry (Grabara and Szopa 2011). The mountain pose is one in which the patient attempts to elongate the spine in the sagittal plane, reducing the normal lumbar and kyphotic curves by engaging muscles to extend the spine vertically. The angle of kyphosis was reduced in patients aged 60 years and older with adult-onset hyperkyphosis (a kyphotic angle greater than 40 degrees) who took part in a 6-month study where they performed yoga for 1 hour 3 days per week for 24 weeks, compared to a control group (Greendale et al. 2009).